A Technical Dissection of the Libra Blockchain

THURSDAY, JUNE 20, 2019 • 17 MINS

My thanks to my mentor and friend Jack Kolb for proofreading this article!

Recently, Facebook has taken a dive into the field of cryptocurrency with the announcement of Libra, a financial service founded upon cryptographic principles and blockchain technology with a long term, grand vision of becoming a unified economic infrastructure on a multinational, global scale. Since its release several weeks ago, there have been plenty of reactions and feedback from news outlets and industry professionals debating the economic ramifications of the Libra organization. Regardless of the debate, Libra's coming out party marks an exciting milestone with regards to the formalization of blockchain technology as a potential solution for enforcing trust, integrity, and authentication in an increasingly digitalized world.

There's been a good deal of comments and criticism targeting the monetary implications that come with Libra's growth. However, in this article, I'll be more focused on summarizing the technical innovations powering the Libra platform, specifically the Libra Blockchain. I'm primarily interested in how Libra attempts to address questions such as how to support scalability and eliminate computational inefficiency (a.k.a. Proof of Work), challenges well publicized by the proliferation of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency predecessors. Additionally, Libra adopts and mirrors smart contracts, an age old idea implemented in Ethereum, allowing client users to create their own protocols for a broad range of business. While the concept of smart contracts has indubitably made blockchain more useful, there have been no shortage of security issues associated with poorly written contracts. I'll also be examining Libra's companion DSL for programming smart contracts called Move! It's an interesting redesign of Solidity that aims to make writing a contract a much safer, yet sufficiently expressive process.

This article's structure is the same as the Libra Blockchain PDF. I only cover the first five sections of the paper. This is because I believe the majority of Libra's differences compared to a traditional blockchain system are found here. Per section, I'll attempt to highlight and analyze Libra's advancements relative to the technical and industry standards reflected by established cryptocurrencies like Ethereum and Bitcoin. I'll try to avoid repeating the paper and keep things concise by focusing on the analysis instead of facts. As usual, feedback and criticism are always welcome in the form of a comment below. Thanks for reading!

1 Introduction

The start of this paper defines some terminology that will be use repeatedly throughout the article.

Libra Coin is the currency for the Libra blockchain. Libra is a fiat currency, meaning that is value is tied to a trove of real world monetary resources. Because of this, Libra should be much less subject to the volatility of traditional cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, where its value is a direct reflection of the market's assessment.

Validators are the entities responsible for processing transactions and maintaining the blockchain's state, similar to the role of a miner. As of Libra's inception, validator membership is limited to the Libra Association, but this will change as Libra changes from permissioned to a truly public blockchain.

Why is Libra going through a permissioned phase instead of just starting off as public? This decision is likely borne from Libra's creators hoping to more easily perform course correction in response to user feedback and nurture Libra's initial growth into a more mature, refined, and tested platform before fully ceding control to the public arena. In addition, because the validators from the Libra Association are known and more likely cooperative, the concern for an anonymous user with malicious intent would not be a tangible issue for now.

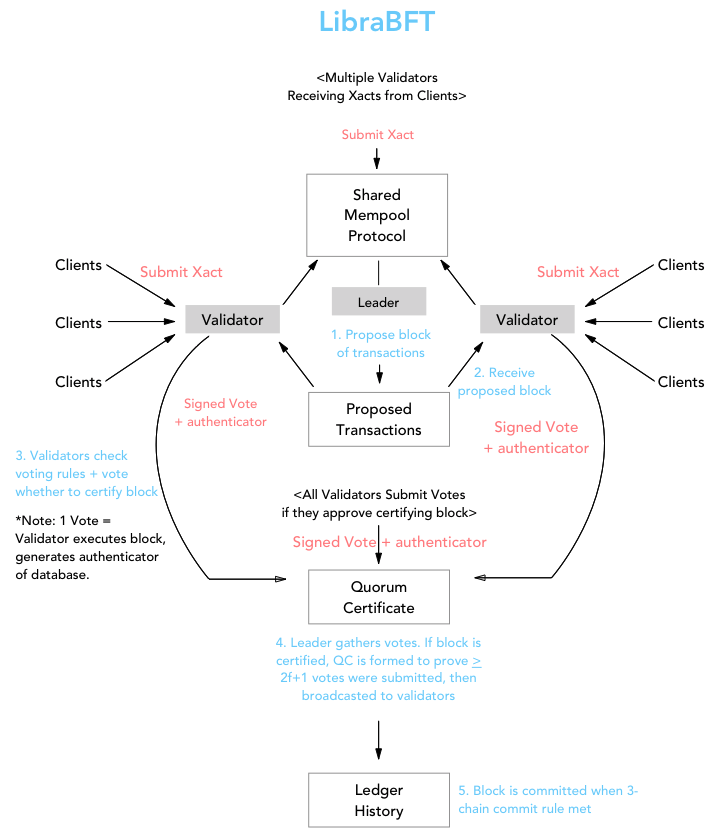

What's more is that instead of Proof of Work consensus, where the miner that gets to add the next transaction is chosen non-deterministically, validators switch off as a leader which proposes transactions submitted by clients or other validators. This setup foreshadows an interesting development towards creating a more computationally efficient consensus protocol, supplanting exhaustive tasks especially like Proof of Work.

The description of the Libra Blockchain is where things get interesting. It's officially defined as a "cryptographically authenticated database that serves as a ledger of programmable resources". However, under the hood, unlike a traditional linked-list-esque structure, the "blockchain" is actually implemented with the Merkle Tree data structure. The "why" and "how" of this will be discussed later on.

The authors also establish some of the objectives that serve as guiding design principles for Libra. One major theme is scalability, as the paper states "The Libra protocol must scale to support the transaction volume necessary...to grow into a global financial infrastructure". Through cryptographic principles and efficient structures, the authors believe Libra can enforce the same rigor of authentication and integrity without nearly as much computing power required.

2 Logical Data Model

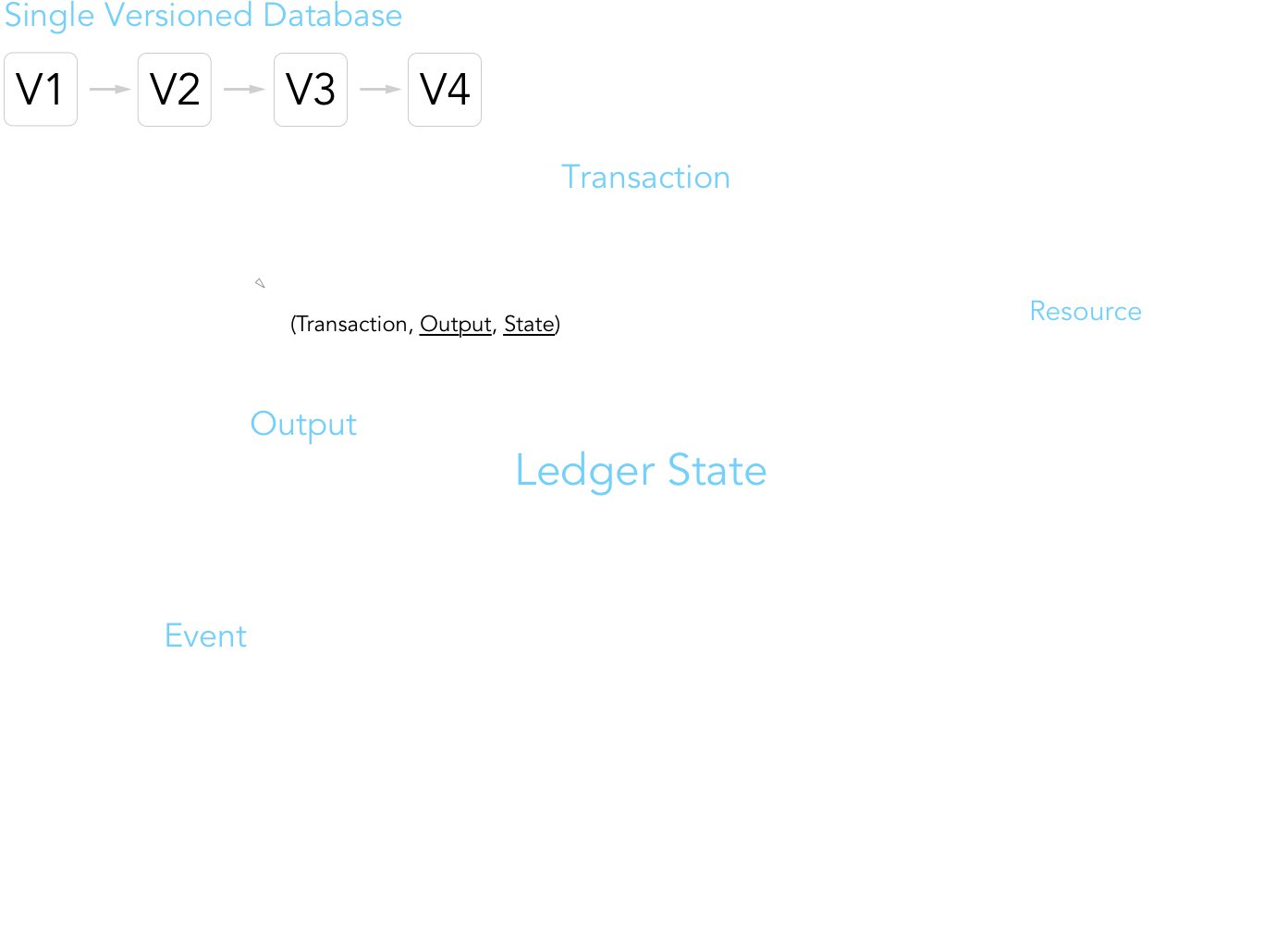

In this section, the authors discuss Libra's general organization and data model. They formalize the terminology regarding an individual ledger state and a transaction. Finally, how these two structures come together to form a historical ledger of states is explained.

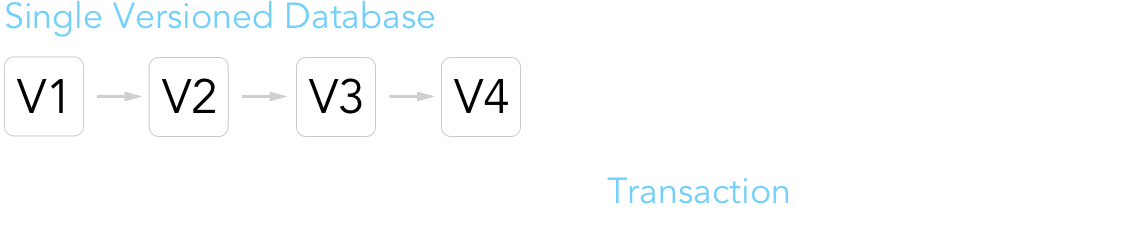

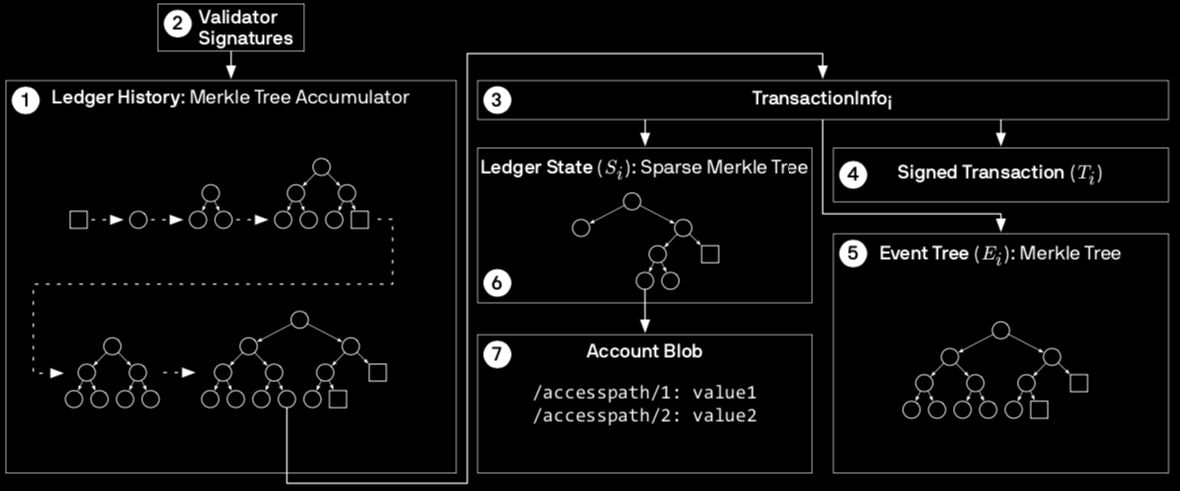

From a high level, the Libra Blockchain can be visualized by the following diagram. For the most part, the general layout greatly resembles a traditional blockchain. One notable difference is that blockchains such as Bitcoin tend to group multiple transactions. However, a block (or in this case, "version") in Libra is distinguished by a single transaction. This model makes it much more straightforward for answering any queries regarding a ledger's state at any version. Incrementing a ledger's state per transactions also provides greater search granularity. Per usual, new transactions can only be added on top the most recent ledger state version.

The next question that might naturally arise is, what goes into a ledger's state? It's really just a simple key-value store associating each account address with a set of resources (data values, i.e. how much Libra Coin does 0x123... have?) and modules (smart contracts, a.k.a. Move bytecode defining a new resource's type + associated procedures. i.e. transfer of Libra Coin between accounts). The below diagram is essentially appropriated from the paper, just with a couple additional illustrations for greater clarity and detail.

The schematics governing account addresses are nothing new. Each user has a verifying + signing key, and the public key, which would be the addresses in the above diagram, is just a cryptographic hash of the verifying key. Resources, broken down, simply associate a resource type (defined by modules) with a particular quantity or value.

A Side Note: The Libra paper states that "each account can store at most one resource of a given type", which was initially confusing to me. If I want to exchange Libra Coin, would I be barred from it because of the aforementioned limitation? After some thought, I realized that in such a situation, the value of the resource would be modified. Such a design has the benefit of eliminating both redundancy and the difficulties that come with fragmentation. In this context, by fragmentation, I mean a situation where there are multiple resources per type.

Notice that a resource is uniquely identified by <account address (creator)> / <module name> / <resource type>. In other words, multiple modules and resources could have the same name, but are distinguished by their creators, making them distinct types. Therefore, in the above diagram, the two coins in account 0x27... have the same module name (Coin) and resource name (Coin.T), but ultimately, are different types (0x27.Coin.T vs. 0x45.Coin.T). I like this convention for identifying resource types because it prevents a first-come-first-serve issue for naming modules or resources (ala domain squatting). Similar to smart contracts, modules wholly define rules for mutating, deleting, and publishing a resource. As of this point, a module published to Libra is immutable, although methods for safe updates are being explored for release in the future.

Ok, now that we've defined state, what about transactions, the medium for going from one state to another? A transaction consists of a transaction script (Move bytecode) + arguments. Section 3 will go into the flow of executing and committing a transaction.

One noteworthy distinction is between an output and an event. An output details information consistently associated with every executed transaction, specifically the new resulting ledger state, gas usage, and execution status code. Events are much more open-ended and defined by the transaction code. This difference highlights an interesting distinction. In Libra, a transaction that is processed and recorded in the ledger history does not imply successful execution. This is where an event helps indicate whether the transaction actually took effect.

Initially, this design was a bit confusing to me. Why record transactions that, if they presumably failed due to an error or running out of gas, don't actually change the ledger state? Upon some additional thought, such a record would be necessary because regardless of the transaction's ultimate output, the validator that attempted to process the transaction still receives Libra Coin for its effort; thus, such a exchange should be recorded. This necessitates events in addition to a fixed set of output fields.

The big picture...

3 Executing Transactions

Now that we've got the data model down, this section explores, to greater depths, the logical and technical flow of transitioning from one ledger state to the next via an executed transaction. Section 3.1 is largely derivative of existing blockchain systems' execution requirements, namely deterministic transaction outputs and metered execution (a.k.a. Ethereum's gas model). Determinism ensures consensus among multiple validators can be achieved. Metered execution, broken down into gas price (Libra / unit of gas client will pay) and gas cost (gas needed to execute Xact entirely), is a technique for preventing Libra from being overwhelmed with too many transactions.

The anatomy of a transaction and its execution by the Move Virtual Machine are detailed below. This diagram is essentially a summary of sections 3.2 and 3.3.

Although the Prologue and Epilogue steps involve running Move bytecode, the client is not charged gas costs for their execution since its is required no matter what transaction is executed. The code is also distinct from the client's transaction's bytecode. Perhaps the most interesting development is Step 3, where the transaction's script and modules are verified. Designing a smart contract involves many safety issues, and in recent years, vulnerabilities such as reentrancy attacks have cost many contract authors and clients a great deal of money. There is much ongoing research in industry and academia designing tools for catching exploitable bugs within smart contracts before they are committed to the blockchain and become immutable. Libra's script + module verification step represents a notable first time where contract checking is being directly integrated in the transaction deployment process. Unfortunately, how exactly contract checking is implemented in Libra is not discussed in greater detail anywhere else in the paper.

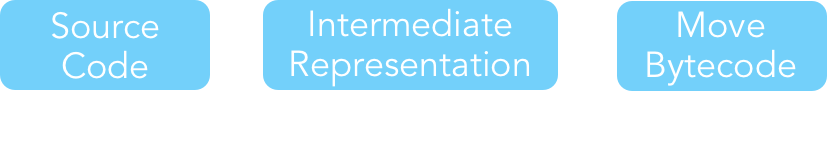

The remainder of this section previews the technical foundations and design motivations of the Move DSL for writing modules and scripts in Libra. The Move programming language can be broken down into three different representations. As of this article, the source language is not available to the general public, so preliminary script and module development can only be written in the intermediate representation, which the authors claim is still human readable.

There are two notable facets of Move that I think are worth pointing out with regards to security. First, the safety checks and guarantees that the Move Virtual Machine performs before processing a transaction (recall Step 3 from above) are enacted on Move bytecode (a.k.a. bytecode verification). This is wise design; performing safety checks at the IR or Source Code level presents an opportunity for malicious clients to evade these checks by simply just writing the code at a lower level. Again, however, how comprehensive these checks are have yet to be elaborated upon by the Libra team.

Another trend is that the more low-level the representation, the more constrained the code base becomes. While the Source Language and IR support more complex paradigms such as conditionals and loops, the bytecode representing these patterns, when compiled, is based on a much smaller instruction set. In fact, the Move VM ultimately supports just six different types and values. I think the authors put a subjectively positive spin on their decision; limiting the instruction set should reduce the scope of potential vulnerabilities, but it comes at the cost of expressivity.

Given that the IR and Source Code language are still very much in development, it will be interesting to see how limitations on the bytecode instruction set affects how expressive the higher level representations can really be. As Libra matures over time, I'd venture that the codebase for all three representations would grow to accommodate more use cases. The Move code available to the public right now is likely limited on purpose, as Libra's maintainers would rather support a safer DSL that is more secure than it is expressive to build trust in the platform.

4 Authenticated Data Structures and Storage

In this section, the authors dive into the data structures behind the data models described in section 2. The Libra Blockchain's technical implementation is dominated by Merkle Trees, and the use of this structure is perhaps its greatest distinction from existing blockchain systems.

Part 1: ADS's and Merkle Tree Basics

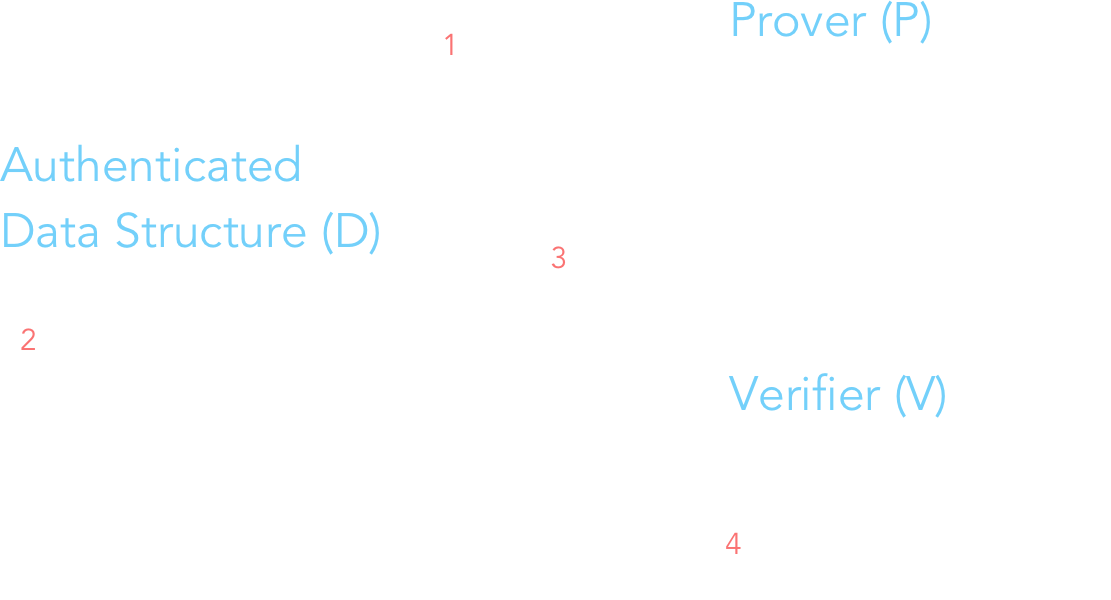

Before diving into how the ledger history, event list, ledger state, etc are stored within Merkle Trees, it's helpful to have a bit of background on authenticated data structures (ADS). For me, this paper was particularly useful for achieving basic comprehension of the motivations, terminology, and technicalities surrounding ADS's in general. I'd recommend reading section 2, which mentions Merkle Trees as a canonical example of an ADS. In one sentence, ADS's are useful because they allow untrusted provers (i.e. validators) to perform operations on and modify the state of the data structure; such changes can be checked for authenticity by verifiers (i.e. clients). In a certain sense, today's most popular blockchain systems can be thought of as a decentralized, distributed ADS. The illustration below depicts a simplified workflow of how provers modify and verifiers check the state of an ADS. The label's letters correspond to the notation used in Section 4.1 of the paper.

What is the significance of a prover being untrusted? After all, as of today, the only validators are verified members of the Libra Association; these validators are, in a sense, trusted. However, as Libra expands later on, the plan is that entities from the general public can become validators. At that point, trust in validators is no longer a guarantee, which is why authentication with untrusted provers modifying the ADS must be tolerable.

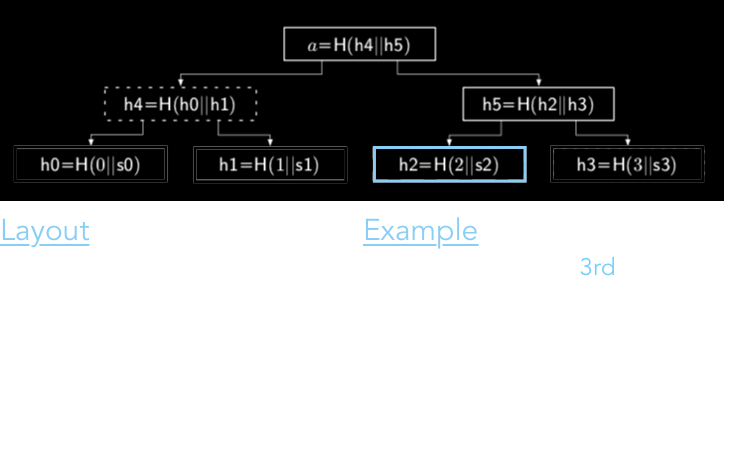

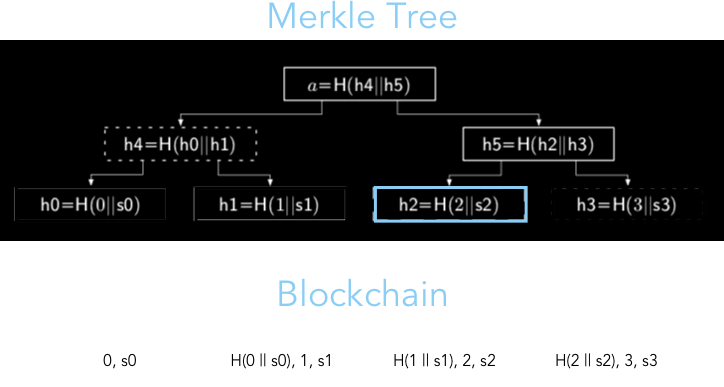

The cryptography of an ADT varies from one data structure to another. So what does a result (R), proof of the computation (π), and authentication look like in the context of a Merkle Tree data structure? Figure 4 in Section 4.1, copy and pasted below with a couple additions, identifies the components of the Merkle tree that correspond to each label.

Recall from the previous diagram, the verifier's authenticator is actually the root node of the Merkle Tree, which is just a hash across the entire tree. As we can deduce from the example above, the proof for any committed state consists of the additional hash values that one would need to calculate the root node's value. To elaborate a bit, for s2, the hashes h2, h3, and h4 would be required to verify authenticity correctly.

Part 2: Implementation

Libra uses many, many Merkle Trees. The Ledger History and each Transaction's Ledger State and Event Tree are all modeled as Merkle Trees. Figure 3 in Section 4.1 is an excellent diagram highlighting the relationships between different components of the Libra Blockchain along with the type of data structure used for representation.

- The Ledger History Merkle Tree's leaves map a version number to a Transaction.

- The Ledger State Merkle Tree's leaves represent the state of all accounts at a particular version. The key is the account's address while the value is the authenticator (hash).

- The Event List Merkle Tree's leaves map an index [J] to a tuple (event [A], data payload [P], Counter [C]). The index indicates the chronological order the events occurred.

- The accounts' contents are stored as an ordered map of access paths (i.e. <account address (creator)> / <module name> / <resource type>) to values.

In the author's discussion, it's apparent that storing Merkle Trees with a tractable amount of data will be a challenge as Libra's history of transactions grows with time. The paper mentions some techniques for minimizing the size of the Merkle tree representation, including pruning, sparse trees, and saving partial representation instead of the whole tree. However, it seems that at this point, there's no way to store a compacted version of Libra's full ledger history.

Part 3: Merkle Tree Pros and Cons

So why not just use a normal linked-list style blockchain? What's all the hurrah over using a Merkle Tree? This change originates out of the drive for scalability and a more efficient authentication process for a client. The diagram below stores the same data using the Merkle Tree data structure and a more traditional, linked list style blockchain.

Let's say that a client who trusts the 3rd block (State 2) wants to verify the authenticity of the 1st block (State 0). In a linked list setting, a client would need to retrieve every ancestor node between the trusted block (State 2) and block in question (State 0), then recompute [# ancestor blocks] hashes (a.k.a. N), simplifying to an O(N) runtime. On the other hand, for a Merkle Tree, only log N hashes are required for authentication.

The runtime of a simple retrieval operation with Merkle Trees is clearly faster than linked lists, but that comes at the cost of space. The diagram also makes it obvious that Merkle Trees many more nodes than a linked list blockchain. A full Merkle tree with N leaves of actual data will required 2*N-1 nodes to store correctly (proof), nearly double the size of a linked list storing the same amount.

This prompts an interesting question. If Libra becomes the global platform it wants to be, just how much storage space would the Libra blockchain require? The paper doesn't provide any quantities reflecting the storage capacity requirements of a single ledger state, a ledger history with N states, or the size of the cryptographic hashes. Without these number, it's difficult to come up with a fair estimate.

Just out of curiosity, let's base the estimation off block sizes from Bitcoin. A Bitcoin block is around 1-2 MB containing multiple transactions. Since Libra's blocks contain a single transaction, we could venture that 1 MB per block is an upper bound. However, for every one Bitcoin block, there will be multiple Libra blocks for each transaction. Therefore, representing the same set of transactions in Libra will likely require more storage in total. Now, if we use the SHA-256 cryptographic hash, we can assume that the hash blocks will be at least 256 bits, an insignificant amount much smaller than a single Xact node. A Merkle Tree's total storage size will definitely be larger than a linked list blockchain, with the majority of the difference coming from the single transaction per block model, and a minor amount due to cryptographic hash blocks. This calculation only considers the ledger history Merkle Tree. I admit, there are many unconfirmed assumptions with the calculation above, but regardless, storage will be constant challenge as the use of Libra proliferates.

5 Byzantine Fault Tolerant Consensus

Let's start with a quick primer concerning consensus. Consensus describes the process in which multiple entities reach an agreement on a unified, single state or data value in a distributed setting. In all forms consensus, there is often a "leader" responsible for proposing modifications to the existing state. Consensus algorithms are ideally designed to tolerate a certain level of crashes and failures, inevitable aspects of distributed systems. Byzantine failures refer to entities or processes intentionally acting maliciously to influence consensus in such a way that benefits themselves (i.e. forks, double spend attacks). Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) algorithms refer to consensus protocols that can tolerate a certain level of Byzantine failures.

There are two primary categories of consensus protocols. Classical consensus algorithms involve participants exchanging rounds of messages containing votes and safety-proofs. The leader is usually elected or rotated out deterministically. Consensus is achieved by majority vote. These protocols work well in authenticated, permissioned environments where the participants are cryptographically verified. More recently, the "Nakamoto" style algorithms popularized by Bitcoin determine the leader (i.e. miner who adds the next block) randomly via a cryptographic puzzle. Consensus in this context is recognized as the "longest chain", or the chain with the most amount of proof of work invested in it. Unlike classical consensus, algorithsm like Proof of Work / Stake / Time still work in public distributed systems where there is no requirement of trusted participants.

So where does LibraBFT sit in all this? Unlike Bitcoin and Ethereum's Proof of Work consensus, the LibraBFT consensus protocol is a classical consensus algorithm. LibraBFT is largely based on the HotStuff consensus algorithm developed at VMWare Research, which in turn is built on top of the Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance Algorithm (pBFT) created at MIT CSAIL. The theory and implementation of these algorithms constitute an entire different field of research that I will not dive into here. The visualization below is my own attempt at showing the consensus protocol works. I think the main takeaway from this section should be that the LibraBFT consensus protocol is, in any sense, randomized or non-deterministic.

Summary

Beyond just the word "blockchain", the implementation and consensus protocols of Libra and popular cryptocurrency systems like Ethereum and Bitcoin could not be more different. The defining traits that we tend to associate today's most popular blockchain systems include the use of linked-list data structures to model a ledger history, along with a non-deterministic consensus protocol functioning in a public setting that randomly elects leaders who can append the new block. While Libra's conceptualized data model has a chronological, linear flow to it, its implementation and consensus protocol differ drastically.

The term "blockchain" seems to be tossed around increasingly indiscriminately these days as a catch-all term to describe the new wave of distributed systems technology. The Libra "Blockchain" is a case in point example of how the word has become a marketing buzzword. I know that sounds negative, but my intention is not to criticize, but rather, to clarify. Before reading this paper, the word "blockchain" prompted expectations of a system more similar to Bitcoin and Ethereum. Instead, Libra's most notable differences are that it

• Is a permissioned, classical consensus-based approach to the problem of building a distributed system operating on a global scale.

• Uses an authenticated, sparse Merkle Tree data structure for everything, not Linked Lists.

• Exercises a classical, elected-leader consensus protocol operating within a permissioned distributed setting.

• Is based on the Move language which redefines the process in which smart contracts (a.k.a. resources, modules, and scripts) are written and checked for safety.

It will be very exciting to see how the move language, data structure implementation, consensus protocol, and additional aspects of the Libra Blockchain evolve over time. Thanks for reading!

References

• The Lineage of pBFT => HotStuff => LibraBFT: Link

• The HotStuff and pBFT papers

• An introductory paper discussing Authenticated Data Structures

• The Libra Blockchain paper link